Romans 5:12-19

Lent is a season of reflection. It invites us to look inward, so we can take stock of our lives. We can ask questions like: Who am I in relationship to God? And, am I on the right path or have I strayed from it? If I’m going the wrong way, how do I get back on track? All of these questions are connected to the way we understand Sin and Death, as well as Grace and Righteousness.

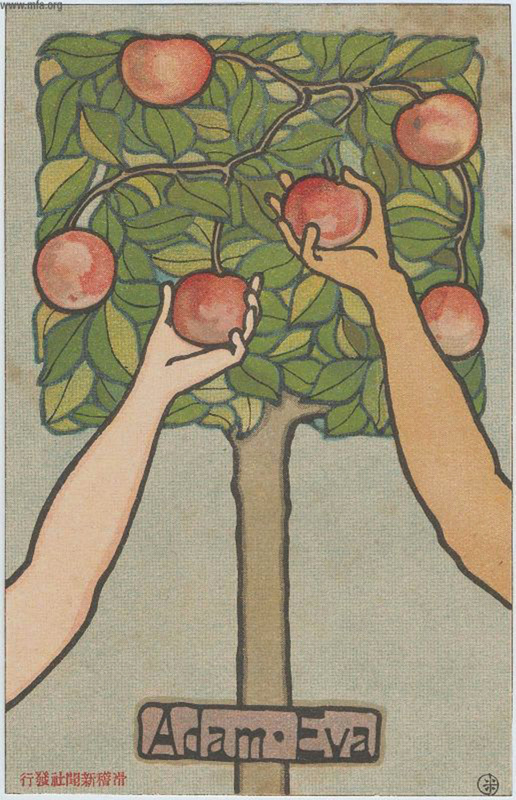

The lectionary readings from the Gospel of Matthew and Genesis tell temptation stories. In Matthew, Jesus goes into the Wilderness where Satan offers him power, glory, and comfort in exchange for allegiance. In the reading from Genesis, Adam and Eve take the bait and eat the forbidden fruit, which leads to their exile from the Garden. In our reading this morning from Romans 5, we start in the Garden, where the first Adam’s act of disobedience opens the way for death to enter human reality, but we end with a word about the Last Adam, whose obedience provides abundant grace and life.

Paul’s writing style can be a bit dense, nevertheless, he offers us a word of hope. We’ve heard the reading from the NRSV, which reflects Paul’s twists and turns. So, perhaps Eugene Peterson’s version of the opening lines of our passage can clear things up a bit:

You know the story of how Adam landed us in the dilemma we’re in—first sin, then death, and no one is exempt from either sin or death. That sin disturbed relations with God in everything and everyone, but the extent of the disturbance was not clear until God spelled it out in detail to Moses. So death, this huge abyss separating us from God, dominated the landscape from Adam to Moses. Even those who didn’t sin precisely as Adam did by disobeying a specific command of God still had to experience this termination of life, this separation from God. But Adam, who got us into this, also points ahead to the One who will get us out of it. (Rom 5:12-14 The Message).

Yes, Adam’s disobedience “landed us in a dilemma.” It “disturbed relations with God in everything and everyone,” which led to separation of humanity with God. This separation from God leads to death. That’s the human story, according to Paul. So, how do we change the script?

Paul tells us that the Law reveals the state of the problem, but it doesn’t solve it. That’s where Jesus comes in. But before we get to the solution, we need to first get a handle on the problem, which is revealed in the question of why we sin. Is it nature? Or is it nurture?

St. Augustine may not have known about genetics, but he did believe that we’re born to sin. It’s who we are, and we can’t do otherwise. We might say that it’s in our DNA, though Augustine blamed concupiscence. That is, he suggested that sin is a sexually transmitted disease, which is why he embraced celibacy. Although he didn’t invent the idea of original sin, Augustine’s views have influenced Western Christendom to this day.

There were challenges to Augustine’s interpretation down through the centuries, but it wasn’t until the dawning of the Age of Enlightenment that a compelling answer to Augustine emerged. While Augustine attributed sin to nature, John Locke argued in favor of nurture. Locke believed that humankind is a “blank slate” on which society writes. He may not have known any more about genetics than Augustine, but he laid the groundwork for people like Alexander Campbell and Barton Stone who rejected the doctrine of original sin. That means we Disciples tend to be nurture people rather than nature people when it comes to the spread of sin and death in the world. If we follow Locke and Campbell, sin might be inevitable, but it’s not genetic. Sin is universal because we’re born into systems that make us susceptible to temptation.

So, if we’re not born to sin, why is it inevitable? Reinhold Niebuhr offered several answers to that question, one of which had to do with anxiety. Do you ever experience anxiety? I do! Does it affect the way you think and act? I expect it does.

Niebuhr wrote that anxiety is “the internal precondition of sin. It is the inevitable state of man, standing in the paradoxical situation of freedom and finiteness. Anxiety is the internal description of the state of temptation” [Reinhold Niebuhr, p. 138]. Now, Niebuhr didn’t believe that anxiety is sin, but it does make us susceptible to sin. He also believed that faith can purge us of this state of anxiety through “faith in the ultimate security of God’s love,” which overcomes “all immediate insecurities of nature and history” [Niebuhr, p. 139]. The problem is that not even the most saintly among us have that level of faith. This means our hope lies in the grace of God, which comes to us, according to Paul, through the obedience of Christ. Yes, “Amazing grace! How sweet the sound that saved a wretch like me!”

When it comes to discussions of sin, like the one we see here in Romans 5, we tend to think in terms of individuals. But, Paul and his spiritual ancestors tended to think corporately. This is true for both sin and grace. Consider Paul’s statement in verse 18: “Therefore, just as one man’s trespass led to condemnation for all, so one man’s act of righteousness leads to justification for all.” Even as we participate in Adam’s act of sin, through our own disobedience, which leads to death, we can participate in the obedience of the Last Adam, Jesus Christ, which leads to salvation and life in its abundance.

If we think of sin in terms of systems, then we can talk in terms of racism, sexism, homophobia, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and other corporate systems. Now, St. Augustine would disagree with this interpretation since he believed that we’re genetically predisposed to sin. He even suggested that only the feebleness of an infant’s body, not its mind, prevents a baby from doing harm to others [The Confessions]. So beware of the child.

However, if we follow Locke’s interpretation then these beliefs and behaviors are passed on by society. We are formed by our context from a young age. Children hear the way parents talk about others, and then they imitate their parents and other adults, until these viewpoints, for good or ill, take root. You might even say that sin and death take the form of a pandemic that features a contagious virus, like the coronavirus. Unless we take precautions, the virus can infect everyone it comes into contact with. In the case of sin and death, washing your hands with soap and water won’t be enough.

If we’re going to break free of these systems, we’ll need to first diagnose the problem. Then treatment can begin. Diagnosis begins with confession. It’s not easy or enjoyable, but it’s necessary. While some traditions regularly include corporate prayers of confession in their worship services, Disciples tend not to include them. Perhaps our reluctance to make confession of sin is rooted in our Enlightenment origins, but if confession is good for the soul, then it’s appropriate to confess our participation in systems of sin.

In recent years, I’ve become aware that our society grants me certain privileges because I’m a white, heterosexual male. I may not have asked for these privileges, but I have them regardless. So, when I drive through a town, I don’t worry about being stopped by the police because of my color. I don’t worry about being followed in a store because of my color. I don’t worry about being asked for my papers when I’m walking down the street.

Chanequa Walker-Barnes has written a powerful book about the problem of whiteness when it comes to racial reconciliation. She writes that too often efforts at reconciliation assume “that White people and people of color are equally responsible for the sin of racial division” [I Bring the Voices of My People, p. 114]. This view fails to take into consideration the lingering effects of slavery and Jim Crow, not only in the South but throughout the country. This is caused in part because of an unwillingness to recognize that whiteness is a racial category.

Even if race is a social construct, whiteness is designed to privilege some people at the expense of others. We may not have owned slaves. Our ancestors might not have owned slaves. Nevertheless, if we’re White, we’ve benefitted from a system built on a foundation of oppression. If we’re going to find healing, we who are White must confess our privilege. It’s not easy, but unless those of us who are granted White privilege make this confession, we’ll remain captive to this system of sin.

There is good news. Grace and healing can be found in Christ. Grace makes healing possible, but it’s through confession of sin, both personal and corporate, that those who have been afflicted by moral injury can find healing for their souls, and reconciliation can begin. As Paul reminds us: “For just as by the one man’s disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man’s obedience the many will be made righteous.”

Yes, “I once was lost, but now am found; was blind, but now I see.”

Preached by:

Dr. Robert D. Cornwall, Pastor

Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christe)

Troy, Michigan

March 1, 2020

Lent 1A

Image Attribution: Hakusui, Komeno. Adam and Eve, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=50235 [retrieved February 29, 2020]. Original source: http://www.mfa.org/.

Image Attribution: Hakusui, Komeno. Adam and Eve, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=50235 [retrieved February 29, 2020]. Original source: http://www.mfa.org/.

Comments