|

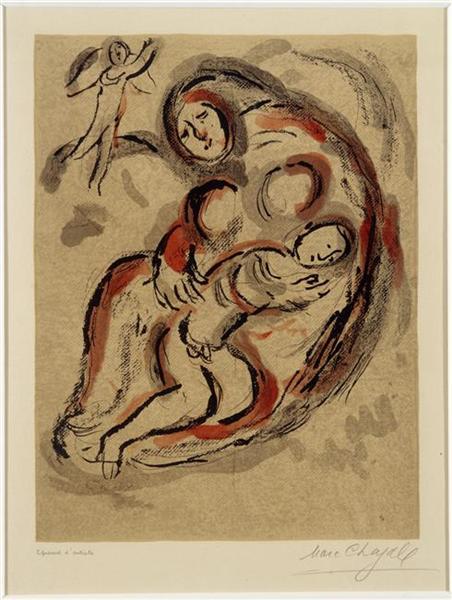

| Marc Chagall, Hagar in the Desert |

Genesis 21:8-21

Today’s reading from Genesis 21 is fitting since Father’s Day is coinciding with World Refugee Sunday. The lead characters in this story include a father—Abraham—two mothers—Sarah and Hagar—and two sons—Ishmael and Isaac. In this story, Abraham sends his firstborn son, Ishmael, along with his mother Hagar into the wilderness, because Sarah doesn’t want Ishmael to share in the inheritance she believes belongs to her son, Isaac. This story is complicated because Ishmael’s mother Hagar was Sarah’s slave, who became Sarah’s surrogate until Sarah had a child of her own. That’s when Sarah decided that Hagar and Ishmael had to go. When Abraham reluctantly agreed to Sarah’s demands, Hagar and Ishmael were sent into the wilderness as refugees. When their water ran out, Hagar hid Ishmael in the bushes and then sat down and wept, while Ishmael cried.

Christian tradition tends to focus on Sarah and Isaac, while ignoring Hagar and Ishmael. This may be due in part to Paul’s rather negative portrayal of Hagar, but it may also be due to the fact that we trace our spiritual ancestry back to Abraham through Isaac and his mother Sarah. Nevertheless, Hagar and Ishmael’s story is important, because it speaks to God’s concern for refugees and offers us an interfaith bridge to our Muslim cousins, who trace their descent from Abraham through Hagar and Ishmael. The promise revealed here in Genesis 21 is that both Isaac and Ishmael will become great nations. The story of Hagar and Ishmael also reminds us that God is concerned about the outsider and the outcast. God cares about the welfare of the refugee, the immigrant, and the stranger. We are invited to share in that concern.

According to the narrative, God hears Ishmael’s cries for help while his mother sat down at a distance so she wouldn’t have to watch her son die. When God sees their predicament, God sends an angel to intervene. The angel reasserts the promise to Hagar first made in Genesis 16, that her son would become a great nation. As Edward Wheeler comments on this scene, “in the midst of life’s injustices it is easy to lose sight of God’s promises. The stress and strain of our predicaments can blind us to the deliverance that is available. Sometimes it takes an intervention from God to help us recognize the salvation at hand” [Preaching God’s Transforming Justice, p. 293.] So, God opened her eyes so she could see the well that would restore their lives, giving them hope for the future. Then we’re told that “God was with the boy, and he grew up; he lived in the wilderness, and became an expert with the bow.”

As I’ve pondered the story of Hagar and Ishmael, I’m reminded that God hears the cries of people in need, including people who live outside our own circles. This reading is fitting at a time when we’re wrestling with the legacy of slavery in this country as well as whether black lives truly matter. It’s fitting because it reminds us that Hagar was a slave and an African. That’s why it figures prominently in the African American churches. It tells the story of God’s liberation of an African slave and her son.

This story has many angles to it, and we could spend hours exploring them. It offers us the opportunity to highlight the role of women in the biblical story. It invites us to consider the question of slavery both ancient and modern. Consider Wilda Gafney’s Womanist reading of Hagar’s story: “I read Hagar’s story through the prism of the wholesale enslavement of black peoples in the Americas and elsewhere; Hagar is the mother of Harriet Tubman and the women and men who freed themselves from slavery.” [Gafney, Womanist Midrash, (p. 44). Kindle Edition].

This story offers us insight into the breadth of God’s love and grace, which is much greater than we sometimes embody, even as it’s greater than what Father Abraham embodied. Nonetheless, there is a word of hope at the end of Abraham’s story. After Abraham died, his two sons came together to bury him. I wonder whether true reconciliation took place in that moment. (Gen. 25:7-11). The Genesis story isn’t clear on that matter and it focuses its attention on Isaac’s descendants. Nevertheless, it contains the promise that God would bless Ishmael’s descendants.

We have the opportunity to embody this dual promise in our own lives as we listen to the voices of those who cry out to God. Might we who are the recipients of God’s compassionate grace share that grace with those who cry out to God, including the refugee, the migrant, and the enslaved? Might we who are Abraham’s descendants find a path to peace in the midst of conflict? Might we heed these words from Edward Wheeler who addresses the ongoing conflicts that separate Abraham’s children?

As we continue to wrestle with deep distrust among Abraham’s heirs and violent power struggles in the Middle East, we must remember that both Jews and Muslims are God’s children. Injustice perpetuated against one by the other robs both of an awareness of God’s promises to all. Just as Isaac is heir to God’s promise, so is Ishmael blessed by God through his relationship to Abraham. [Preaching God’s Transforming Justice, p. 293].

Abraham might not win Father of the Year, and the reading for next week will reinforce that feeling. Nevertheless, this story reminds us that God will be present to those in need, including the exile and the refugee. It also reminds us that there is another branch of the family tree to get to know. Then together we can share in the promises of God and then embody the blessings of these promises in our daily lives as we live together in fellowship with the God of Abraham, Hagar, and Sarah.

Preached by:

Dr. Robert D. Cornwall, Pastor

Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

Troy, Michigan

June 21, 2020

Pentecost 3A

Comments