While I once lived in a small town when I was a child, I’ve lived most of my adult life in cities. I started life in Los Angeles and lived briefly in San Francisco, but my first true memories are connected to my childhood in the small town of Mount Shasta. Although I tasted small-town life before I ever experienced city life, I know what it means to be a city boy, if you count the suburbs as the city! So, what responsibility do we have as suburbanites for the welfare of the city? That’s our question for today!

We’ve heard a word from the prophet Jeremiah, who wrote a letter to Jewish exiles living in Babylon. These exiles included the elders, priests, prophets, and everyone else whom Nebuchadnezzar sent to Babylon in the first wave of exiles who accompanied King Jeconiah and his mother. This was before the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple a decade later. At that point, the exiles still hoped they could return to their homes in Jerusalem. Nevertheless, Jeremiah wanted the exiles to know that their exile would last a long time. He told them to ignore the false prophets who were telling them they would be going home very soon. Instead, to borrow from a1960s slogans, he told them to “bloom where you are planted.”

The experience of these exiles isn’t so different from what exiles and refugees and migrants have faced through the ages. We might think about the recent wave of Afghan refugees who know that they probably can never return home. The Venezuelan asylum-seekers who ended up on Martha’s Vineyard might also identify with these exiles. What these and other migrants and refugees and exiles have faced throughout history is how to make a life in a strange land. Yes, how might they “bloom where they’re planted?”

While I’m not an exile or an immigrant or a refugee, I’ve tried to listen and understand the realities faced by those who move from one land to another. Just the other day I heard a word about life on the California-Mexican border, where many gather hoping to find a new life north of the border. Many are refugees. Their situations are dire. I’ve also learned a lot about what it means to be an immigrant from friends who come from places like India and Pakistan. I’ve heard their struggles. But they have tried to bloom where they’ve been planted.

One of my closest friends is an immigrant from India who serves as the first Hindu woman in the Michigan House of Representatives. We’ve had many conversations about what it means to be an immigrant. While she’s definitely bloomed during her years in the United States, it’s not been easy.

While most of us here today might not think of ourselves as exiles or migrants living as strangers in a foreign land, Jeremiah invites us to put ourselves in the shoes of the Jewish exiles living in Babylon. He invites us to put down roots and take responsibility for the world we inhabit.

One of the questions the exiles faced was a theological one. Many cultures have assumed that the gods are bound to specific geographic areas. So, while Yahweh might be the God of their homeland, did Yahweh travel with them to Babylon? In a world where “church and state” were intricately intertwined, they had to wonder whether they should pledge allegiance to Marduk since Babylon was his territory.

While things might look bad for the people, Jeremiah wants them to know that Yahweh had indeed traveled with them to Babylon. Therefore, he called on them to put down roots so they could serve as Yahweh’s representatives in Marduk’s territory.

Since this would be a very long exile, Jeremiah wanted them to settle in by building houses, getting married, and having kids. In this time of uncertainty, they should carry on as the children of Abraham, Moses, and David even as they lived far from their homes and Temple in Jerusalem. While the people might be heartbroken over their situation, Jeremiah wanted them to know that God had a job for them during this difficult time. In fact, these exiles had a priestly responsibility for the land they were currently inhabiting. That’s because since they were still God’s covenant people and because God is faithful God won’t abandon them. Therefore, God wanted them to seek the welfare of the city they inhabited.

If they were going to fulfill their calling they would need a new vision that would empower them as they followed Yahweh into an unknown future. Song Mi Suzie Park puts it this way:

In the face of this religious upheaval, Jeremiah encourages the community to continue to have faith in God’s larger plan—a plan that seems utterly impossible, but which Jeremiah hints is possible for God. They are to hope and know that God can and will bring God’s promises to pass [Connections, p. 377].

A few chapters later, Jeremiah reveals that new vision in the form of a new covenant God would write on their hearts rather than on stone (Jer. 31).

While this word about a new covenant was meant for the exiles, early Christians interpreted their experience with Jesus in light of this promise. While Jeremiah might not have us in mind, Paul suggests that we’ve been grafted onto the vine that is Israel so we too can participate in God’s covenant promises (Rom. 11:17).

The key to understanding what Jeremiah had in mind is found in verse seven. In a verse that I believe has powerful relevance for us today, Jeremiah counsels the exiles to “seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the LORD on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.”

Here is where blooming where we’re planted comes in. This call to become engaged with where we live and work doesn’t require us to take dominion over things, something the exiles couldn’t do. Instead, by pursuing the welfare of the city we pursue the common good of all. In this we find our own welfare. That means we’re all in this together!

I know you’ve been involved in these efforts as a congregation down through the years. I got to partner with you during my ministry at Central Woodward. That included helping create the Metro Coalition of Congregations more than a decade ago. We never got very big but we did some good work on behalf of the city.

When we seek the welfare of the city, those of us who are citizens can make use of our rights to register and vote. We can join together in faith-based community organizing or interfaith work just to name a couple of possibilities. We do this, as Jeremiah reminds us because our welfare is tied to the welfare of the larger community. As people of God, we engage in this work not by using worldly power, but by depending on God’s Spirit so we can make a difference in our communities.

There is a hymn in the Chalice Hymnal by Eric Routley titled “All Who Love and Serve Your City.” This hymn reinforces the message of Jeremiah:

In your day of loss and sorrow,

in your day of helpless strife,

honor, peace and love retreating,

seek the Lord, who is your life.

The hymn closes with a conversation with the “Risen Lord” who answers the question “shall yet the city be the city of despair?” with a promise:

Come today, our Joy, our Glory:

be its name, “the Lord is there.” [Chalice Hymnal, 670]

Yes, the “Lord is there,” even in Babylon.

While this is good news, it also reminds us that we have a responsibility for the welfare of the city we as God’s people inhabit. So, whether or not we’re refugees, immigrants, or exiles, we can heed this word from Miguel De La Torre, who points out that Jeremiah isn’t asking the exiles to forsake their identity, heritage, or their God. Neither is Jeremiah asking them to assimilate into the surrounding culture. So, he writes:

Jeremiah does not call the exiles to stop being Jewish or worshipping their God. Rather, as foreigners, we are to work for the common good of all who also inhabit the land where we find ourselves. Foreigners should be willing to learn from the land’s inhabitants, in the same way that the natives of the land can learn from the stranger in their midst. [Preaching God’s Transforming Justice, pp. 427-428].

Could it be that we are both guests and hosts at the same time? If so, can we be equally blessed in both roles? If I understand Jeremiah correctly, that would be true!

Preached by:

Dr. Robert D. Cornwall

Pulpit Supply

Congregational Church of Birmingham

Bloomfield Hills, MI

Pentecost 18C

October 9, 2022

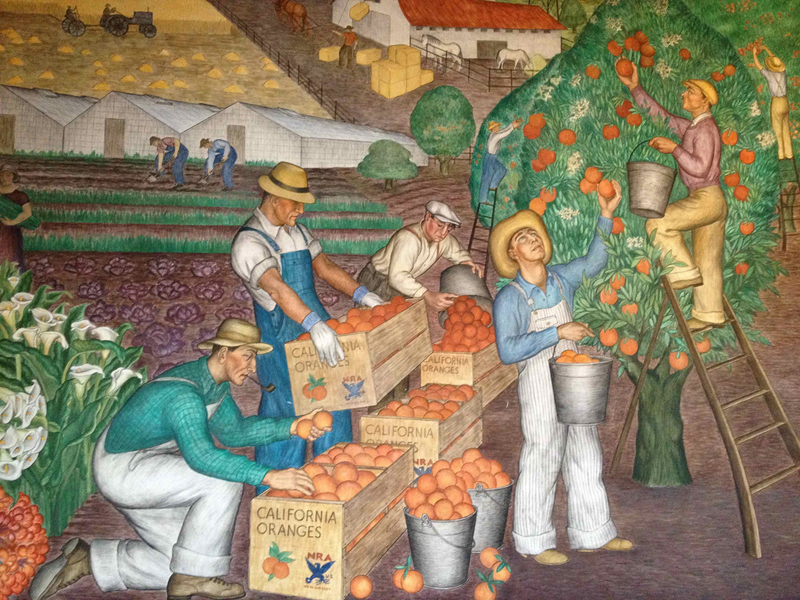

Image Attribution: Migrant Farm Workers, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56609 [r

Comments