|

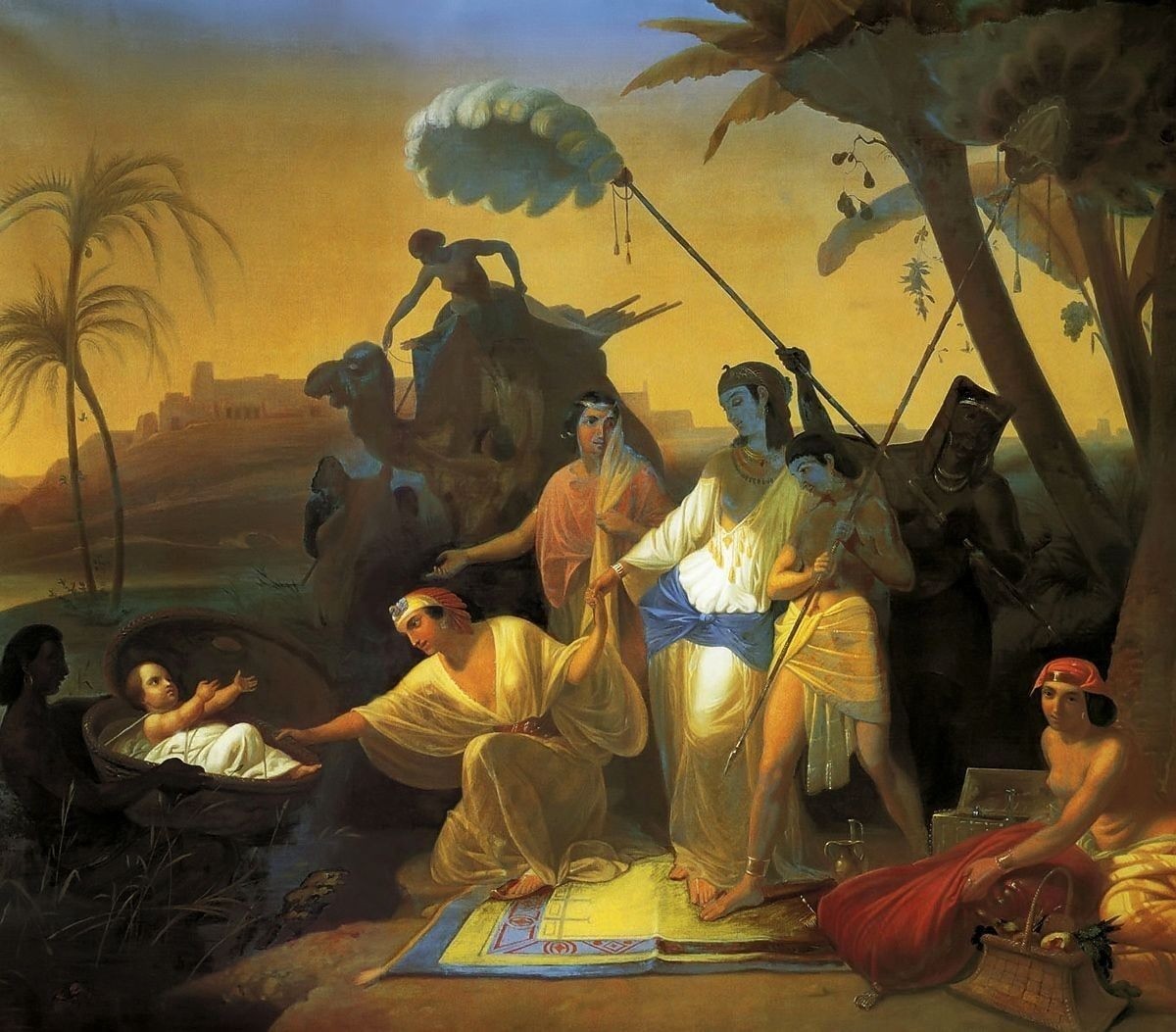

| Pharaoh's Daughter Finding Baby Moses Konstantin Flavitsky, 1855 |

When God appeared to Abraham in Haran, God asked him to pick up and move to an undisclosed location. In exchange for heading out on this adventure, God promised to make his descendants a blessing to the nations (Gen. 12:1-9). As the story goes in Genesis, Abraham and three generations of his descendants carried that promise forward. Due to famine and the providential placement of Jacob’s son Joseph in a position of power, Jacob’s family ended up in Egypt where Joseph was Prime Minister. Although Joseph ended up in Egypt because of some family dysfunction, his presence in Egypt brought blessings to his family and to the nations.

When we turn from Genesis to Exodus, Abraham’s descendants still reside in Egypt. In fact, it’s four hundred years later and the family has been fruitful and multiplied. Their fortunes were about to change because a Pharaoh came to the throne of Egypt who knew not Joseph (Exod. 1:8). Pharaoh grew rather concerned about the presence of this group of non-Egyptians in his realm. He was concerned that if the trend continued, these Hebrews might someday outnumber the native Egyptians. Besides if Egypt’s enemies invaded, the Hebrews might side with the enemies. It seems that this new Pharaoh who didn’t remember Joseph bought into what some call the “Great Replacement Theory.”

As you may know, there are many in North America and Europe, who embrace the “Great Replacement Theory.” This theory suggests that if immigration is left unchecked before too long White Christian culture and dominance will be wiped away. So, while we might want to welcome a few more Northern Europeans, we should let in fewer Asians, Latin Americans, and Africans. You know, people who don’t share our Euro-American Judeo-Christian values.

In these opening stories from Exodus, not only does Pharaoh buy into the conspiracy theory, but he decides to “deal shrewdly” with these Hebrews. So he ordered the enslavement of the Hebrews, who were put to work building two new cities and bringing in the crops to fill his new granaries. He hoped that by dealing ruthlessly with the Hebrews he could stem the tide of their population growth.

Unfortunately for Pharaoh, his shrewd plan didn’t work. The more he oppressed the Hebrews, the more they multiplied and spread across his empire. Since slavery didn’t slow things down, Pharaoh decided to try even more drastic measures. He called in the Hebrew midwives and ordered them to cull the Hebrew population by killing off the boys born to the Hebrew women. Since Pharaoh’s word was law, what were the midwives going to do? Will they obey Pharaoh or God?

According to the story, the midwives who were named Shiphrah and Puah feared God more than Pharaoh. So instead of killing the boys, while sparing the girls, they let the boys live. When Pharaoh realized that this plan wasn’t working, he called in Shiphrah and Puah and asked them why the Hebrew women continued to produce baby boys? The midwives told Pharaoh that the Hebrew women were more vigorous than Egyptian women so that by the time they reached the mother, she’d already delivered the baby. It was too late to kill the babies since the mothers already held them in their arms. It seems that Pharaoh bought their story. As for Shiphrah and Puah, God blessed them with families of their own. This is how Kelley Nikondeha describes the aftermath of their defiance, “God blesses them and other Hebrews with families, allowing them to continue to be fruitful and multiply despite the genocidal climate” [Defiant, p. 33].

Now, Pharaoh wasn’t going to give in that easily. He believed he was facing an existential threat to his rule. He wasn’t going to let these foreigners displace his people and undermine Egyptian culture. If the midwives weren’t going to help him, then he would order the entire citizenry to help him stem the tide of foreign influence. So, he issued a decree, ordering his people to throw every newborn Hebrew baby boy into the Nile, though once again they could spare the baby girls. The irony of this story is that it appears Pharaoh didn’t think women could be a threat, and yet the women defy Pharaoh’s attempts to eliminate the Hebrew people.

Pharaoh was more successful in his efforts to rid himself of this perceived threat. He got his subjects to join his plan of extermination by playing on his people’s insecurities. It’s the same playbook that Hitler used when he tried to implement his genocidal plan to exterminate Europe’s Jews. If his plan was going to work, he had to convince the people that dark forces threatened the survival of the nation. Yes, Pharaoh tried to convince the people that the Hebrews were a security risk.

Might something similar be happening in our country? Could political forces be at work in our midst trying to drum up fear of the other, whether the “other” is a person of color, a Muslim, Jew, Gay or Lesbian or Trans., socialists, Chinese and other Asians, Mexicans and Latin Americans, African Americans or some other group of people that get added regularly to the list? Contemporary American proponents of the “The Great Replacement Theory” are working hard to make sure that the “other” doesn’t replace the dominant role that good white Christians play in our society.

Pharaoh did his best to devise shrewd plans to defeat his perceived enemies. But none of them seemed to work. The midwives refused to obey Pharaoh’s orders. While many loyal Egyptians probably obeyed Pharaoh, we see further signs of resistance as we turn to Exodus 2.

In chapter 2 of Exodus, we hear the story of one family’s resistance, which led to a basketful of blessings. There was this family from the tribe of Levi who decided to have another child despite Pharaoh’s orders. When they discovered that the baby was a boy they hid him for three months. When they could no longer hide him, they devised a plan to save the boy.

The baby’s mother placed the baby in a basket and set the basket among the reeds along the banks of the Nile. The baby’s older sister, Miriam, watched over the basket until Pharaoh’s daughter came to bathe. When Pharaoh’s daughter, saw the basket, she opened it up and saw the baby and she had compassion for him. While she knew that this was one of those Hebrew boys her father had ordered killed, she decided to defy Pharaoh. She picked up the baby and accepted the boy as her own son. Because the baby hadn’t yet been weaned, Miriam approached Pharaoh’s daughter and asked if she would like a Hebrew woman to nurse the baby? If so, she could find a wet nurse, who turned out to be the baby’s mother.

Despite Pharaoh’s efforts to eliminate the Hebrew threat, several women beginning with Shiphrah and Puah exhibited greater shrewdness than Pharaoh displayed. When the baby reached the appropriate age, the baby’s mother returned the child to Pharaoh’s daughter who named him Moses, because she drew him out of the water.

Kelley Nikondeha celebrates this act of adoption by reminding us that while women are often unnamed in the Bible, the baby’s mother’s name will eventually be revealed as Jochebed. While the Bible doesn’t name Pharaoh’s daughter, Jewish tradition gives her the name Bithiah, which is translated as Daughter of God. When it comes to Bithiah, Kelley writes:

Bithiah received Moses as an unexpected gift. He, in turn received maternal love from her as he grew and matured. His Egyptian mother, who knew him to be Hebrew utterly other and different from herself, offered him daily care and unequivocal acceptance. And his dual identities became a pivotal gift that God empowered for a future act of emancipation. [Adopted, p. 52].

Here in chapter 2 of Exodus, we hear the story of three more women, Jochebed, Miriam, and Bithiah, who defy Pharaoh’s orders, even though Pharaoh didn’t think women were a threat to his power.

Because these women defied Pharaoh, a baby would be drawn from the water and given the name Moses. Moses would grow up to become God’s agent of liberation for God’s people. Therefore, the promised blessings would be passed on to future generations.

We live in an age when forms of Christian nationalism, white supremacy, and fear of the other run rampant in our society. Therefore, this story of defiance has much to offer us. It provides us with a lens through which we can view the “foreigner.” Perhaps it’s the child of a despised “foreigner” whom God will use to further God’s ultimate purposes. You never know how these things will work out. Whether we’re the “native” or the “foreigner,” perhaps God is calling us to nonviolently resist these forces of exclusion and oppression.

I turn again to the wisdom shared by Kelley Nikondeha. She writes that “the women of Exodus remain strong archetypes for us as we enter into the liberative work of our own era. They help us crack open our imaginations for the long walk of freedom that remains ahead” [Defiant, p. 184].

When Pharaoh’s daughter drew that basket from the Nile, she discovered it contained an agent of God’s blessings for the nations. Her willingness to defy her father, the Pharaoh, meant that God’s promise to bless the nations through Abraham’s descendants would continue on for another generation.

If you look at Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus, you’ll notice it starts with Abraham. That suggests to me that the promise of Abraham extends to Jesus, Abraham’s descendant. Then, if we turn to Paul’s letters, we learn that those of us who are Gentile Christians, have been adopted into Jesus’ family. Therefore, as adopted members of Jesus’ family, we too have been commissioned to carry a basketful of blessings into the world (Gal. 3:27-29). May this be our calling!

Preached by:

Dr. Robert D. Cornwall

Pulpit Supply

Congregational Church of Birmingham (UCC)

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

Pentecost 13A/Proper 16A

August 27, 2023

Comments